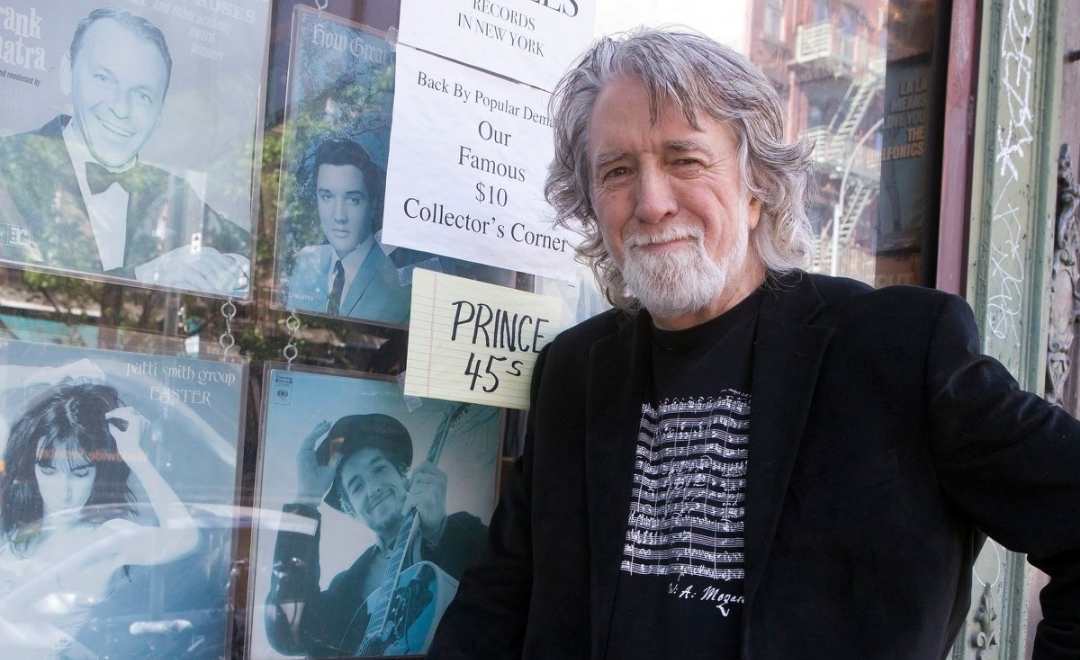

It is a sincere honor to be joined this week by John McEuen of Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. John is one of the most celebrated and best known banjo players in the world, and has had a long and exciting career in music. It was amazing to get to speak with him about his book, “The Life I’ve Picked,” his early days at the magic shop in Disneyland, and about being the first American musical group to tour Russia in 1977.

I really enjoyed talking to John about his many adventures with the band and his time recording albums. It was especially interesting to hear about his experience in the USSR. John 200 photos from that tour, and he is going to release them in a book that comes out in 2021 entitled The Russian Trip. He also has a second book coming out titled 50 Years- The Circle Album Keeps Going, which features almost 100 photos from the recording sessions for Will The Circle Be Broken – Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s 1972 album hailed by Rolling Stone as the most important record to come out of Nashville.

Even more fun was finding out that John had once lived in the same neighborhood that I live in now. And I loved his insights on how he’s finding joy and keeping busy during the pandemic.

Joy in the Messy Middle

Being a performer, and being drawn to create music for others, it was really interesting to hear about how John re-centers during hard times.

“My purpose is I sit at home and maybe come up with a new lick and think, “I can’t wait to get this out in front of people to see if they like it.” Once I either make it up or I learn the song, I don’t want to sit around and play it for me, I’m pretty bored with that. I have to go out and do it for somebody and make their life react to it. It’s like a magic trick.

If I learn a magic trick in front of the mirror and I’m doing it all right, what good is a magic trick if you just do it for yourself? You’re not going to fool yourself. I know how you did that. Of course, I’m me. You have to take that trick out and do it for people. The trick, in this case, would be a song or a story, or a joke, or something.”

In this interview, John McEuen and I talk about:

- John’s first job at Disneyland’s magic shop, where he met and became friends with Steve Martin

- His early days playing the banjo

- The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and visiting Russia in 1977

- The role that American music had in bringing down the wall and opening up Russia

- His book, The Life I’ve Picked, and his upcoming books

- The “Made in Brooklyn” album

- Three ways to jump start your joy: making children laugh, connecting with people through music, giving people and things a chance

Resources

The Life I’ve Picked: A Banjo Player’s Nitty Gritty Journey

John McEuen’s website

John McEuen on Facebook

Did you love this episode? Consider buying me a “Cup of Coffee” to support the show.

Transcript of Interview with John McEuen

Paula Jenkins: I am so very excited to have John McEuen on. Welcome to the show, John.

John McEuen: Thank you. It’s good to be talking to someone in my old home turf of Fremont.

Paula: That’s right. We just discovered that you probably lived just a few blocks from where I’m sitting right now. That’s really exciting.

John McEuen: It was for me in seventh and eighth grade, too. It was a new development. We lived there for a couple of years and then moved to southern California. I was a kid, so I didn’t have much to say about it. I was just glad that we were now only two miles from Disneyland, where I ended up getting my first job. At 16 years old I wanted to work in the magic shop in Disneyland. By the time I convinced them I was 16 and I got the job, along with Steve Martin. We were both trying to get a job there. It was the best three years of our early life – of our life, probably.

Paula: You guys are still friends, having met there at Disneyland?

John McEuen: It started at Disneyland. Then we were seniors in high school together in Garden Grove High School. Then we went off to do things, he went to four years of college, I went to two years of college and started a band. Nitty Gritty Dirt Band got going. Then Steve got going and my brother managed him in his early career, his first 15 years, his first movies and TV shows and stuff.

It was very strange to have a guy that you got a job in a magic shop with, where you were really excited about making $1.10 an hour, and if you worked 50 hours, you’d get $1.25 overtime. I’m glad to say that I got a lot of overtime. It’s very strange to have a friend such as that for so many years that is now probably worth half a billion dollars, and I’m not, but I’m doing fine.

Paula: You have recently, or maybe it’s not really united, but I believe that Steve has played on your album, and of course now he plays the banjo himself. Can you talk a little bit about that? It must have been a really amazing full circle type of moment, too.

John McEuen: It really was. Steve and I started playing the banjo at the same time. Two different banjos. I was able to learn things faster than him, so I showed him what I was learning. He kept up pretty good and then he started writing his own songs.

Keep in mind these are a couple of young guys, this is at 18, 19, 20 years old. It wasn’t until I was 20 that the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band got underway, in which I was the oldest member, the ages were 16 through 20. That went by for a few years. Steve kept playing the banjo and started performing live around the area, trying to figure out what to do.

Let’s just fast forward to 2010 when he had written a bunch of tunes. I said, “I ought to produce an album on you,” and he said, “That’s a good idea.” He called it The Crow: New Songs for the Five String Banjo, and it won a Grammy. I was proud of that. Over the years, I’ve done music for a couple of his specials and played with him several times.

He has written a wonderful foreword for my upcoming illustrated book, The Mountain Whippoorwill, which is a poem that I do while I’m playing fiddle and then I pick up the banjo. He wrote a foreword for it because we learned that in high school, senior year, and it’s been with us all our lives. It’s a seven-minute poem with music behind it. I have an illustrated adult children’s book coming out next year with The Mountain Whippoorwill. That’s a good thing. Maybe I’ll win something. I don’t know.

Paula: That’s amazing. I understand you have another book coming out in 2021 and it’s about when the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band went to the Soviet Union in 1977. You have a lot of photographs from that time, and some of them haven’t even been seen before.

John McEuen: 1,700 black and white, 200 color, out of which there’s going to be about 150 black and white and maybe 20 color. It tells the story, along with me telling the story, of being the first American band to go to Russia in 1977, where we did 28 sold out shows. It was incredible, it was really fun.

Paula: It seems like you were some of the first and then things started to open up, a lot of rock bands went in after you guys were there. What was it like being in the Soviet Union as one of the first American groups to be there?

John McEuen: They didn’t know many American groups. The music was illegal, it was illegal to import things that weren’t approved, it was illegal to have albums, clothing, anything. It was restricted. You couldn’t use Russian money anywhere else in the world but Russia, and it was a three-year jail sentence if you had possession of foreign currency. If you wanted to buy a record that’s going to cost $10, “I have to find $10.” “Hey, this guy over here has $10.” Arrest him.

To get it into the country, it was such an arduous thing. They even had “bones records.” Now, bones records are something that is a little unusual. “I go to London next week to get x-ray,” because they don’t have the right x-ray machine in Russia, people were allowed to go get x-rays. They wouldn’t say it, but they knew what he was doing.

He would go get his x-ray and then he’d take the x-ray film, which is about 14 x 25 or 20, and it was thick and heavy, and then they would record a record on it. They’d put it on a turntable and record on it, so it would have a bunch of grooves on it. It was like a record you used to get in a magazine, a little paper record or something.

When they’d come back into Russia, they would bring their x-ray with them and the KGB is stupid, they’d look at it and think it was just an x-ray, but it was an album of The Beatles or whoever they could capture. It would play maybe twice, so they were ready to record it with recording machines when they got it over there. This was in the ‘70s and the ‘80s. It was quite a thing to have American music.

Voice of America Radio, very important, very much jammed by the Russians. Radio stations didn’t exist; radio station did exist, one station in every town. All the radios in a certain town were tuned to that station, the Leningrad station, the Moscow station, et cetera. They were different frequencies, and you’d buy a radio with that frequency and listen to the radio. You’d just turn it on and there it was, you didn’t have to go looking for it. There was not a station dial. I always thought I wonder if any Russians defected to New York and went out and bought like 80 radios thinking so many stations here.

We signed some albums. I signed a 15 year old Temptations album and an Aretha Franklin album that was 10 years old. It was a great time. It was like being a combination of The Beatles and Credence Clearwater and the Dirt Band. We did a Chuck Berry song. We did Georgia on My Mind. We took a female singer with us.

Let’s just put it this way. The shows went over so well, playing to 2,000 – 5,000 people a night depending on the venue we were at, that they didn’t let anybody else in for eight years. Rock-n-Roll, the communist plot to overthrow capitalism. No. It’s the American plot to overthrow communism.

Paula: I know there have been some documentaries since then that have arguably stated that allowing American music in was one of those things that brought communism down as it stood.

John McEuen: The people involved in that tour said there were two things that helped bring that wall down and change things. One was music and one was the fax machine. When the fax machine came online, you could send pages of information in seconds before it got jammed.

Paula: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t even thought about the fax machine having an impact.

John McEuen: 1988 or 1989 the fax machine came along, and it would get stuff out there. A guy with a fax machine could receive, too.

Paula: In looking forward to your book and some of the photos of that tour, what are some of the things that people can look forward to and expect in the book that you’re putting out?

John McEuen: They can expect to look at something that was 45 years ago and it looks about the same now. It’s just an interesting look back at a band when it was at its prime. There have been five different primes, career swings, upswing, downswing, up, down, up. After 50 years of doing that, I left to work on my own and to talk about my new stuff and write books about the old stuff.

I have a book out called The Life I’ve Picked, which basically takes me from beginning to right around now. I don’t want to say to end. It covers the early playing, the Dirt Band, what went around the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band thing, and the other people that I’ve played with, from Leon Russell to Roy Acuff, to just a long list of people.

Paula: I know in another interview you mentioned that you thought the theme of the book or the through line for the stories that you pulled together was that you got to live the dream, and you still do, but it doesn’t really feel like you’re working for a living. Is that how you would still interpret that piece or what it says about your past?

John McEuen: I realized that the magic shop was so much fun that I used to be sad that I would only get 50 hours in a week. I usually got 60 hours. Then I’d get my paycheck and that was fun, too. The point was that it wasn’t work, it was doing something I loved. As long you’re doing something you love. You have to make some money, but if you’re doing something you love and you make some money, you might make a lot more than you thought you were going to. That makes it even more fun.

Being able to do something that people actually go out to see is really a responsibility. I always feel like there’s people in that audience that have put the ticket on their refrigerator a month ago, two months ago, three months ago, and they’re thinking, “There’s the ticket. I’m looking forward to that show. I hope he does…,” whatever. Then it’s a real responsibility I have to the audience.

It doesn’t matter if you don’t feel well or if you’ve had trouble at home or somebody is sick, or whatever. You’re there for their two hours. I could have a migraine, as I used to in the early years, and doing a show would make it go away because it’s such concentration.

Paula: That’s fascinating. I hear that in the stories you just told. I don’t know if you want to talk about how you found your way to connect with other people or find a happy way out of a hard place.

John McEuen: My purpose is I sit at home and maybe come up with a new lick and think, “I can’t wait to get this out in front of people to see if they like it.” Once I either make it up or I learn the song, I don’t want to sit around and play it for me, I’m pretty bored with that. I have to go out and do it for somebody and make their life react to it. It’s like a magic trick.

Paula: That’s a good through line right there.

John McEuen: If I learn a magic trick in front of the mirror and I’m doing it all right, what good is a magic trick if you just do it for yourself? You’re not going to fool yourself. I know how you did that. Of course, I’m me. You have to take that trick out and do it for people. The trick, in this case, would be a song or a story, or a joke, or something.

Paula: About your creative process, it sounds like sometimes things kind of just come to you. How do you go about creating something new, whether it be a book, a song, a melody, or something else that you share with others? What is your creative process, how do you get it going?

John McEuen: I have to admit that with COVID happening, it is very difficult. I very much appreciate your phone call and your questions, because that is more fun than sitting around the house. Sitting and writing something, I’ve come up with maybe two songs.

I’m just like anybody else. I’m trying to figure out what to do that I would look at a year from now and go, “I’m glad I wasn’t just binge-watching some show, like Frankie & Grace or something,” which I already did. Have you seen Frankie & Grace?

Paula: I’ve seen part of it. We’re currently going through Little House on the Prairie again.

John McEuen: Binge-watching should be a sport. In between different things, it’s fun to find things. That’s why I like working on things.

I have an album that’s all talk that is almost done, it’s an all spoken word album that has music behind each piece. One of them is a letter from a guy in the Civil War writing to his wife with like film score music behind it.

Another one is a letter from a guy in Vietnam writing about taking Nui Ba Den. That was really a tough one to read, because this is from a guy in the field. Anyway, it really came out good.

Another is Fly Trouble, a Hank Williams song, “Did you ever sit straight up in bed with something circling around your head? You swat at it as it whizzes by, and it’s just one pesky little fly,” and that story goes on with music behind it, totally different music.

One of the pieces, have you ever heard of The Cremation of Sam McGee?

Paula: Yes, I have.

John McEuen: You have? Do you remember any of it?

Paula: Only vaguely. I know I’ve heard it.

John McEuen: There are strange things done in the midnight sun by the men who moil for gold. The Arctic trails have their secret tales, and it would make your blood run cold. Those Northern Lights, they’ve seen queer sights, but the queerest they ever did see was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge, I cremated Sam McGee.

That has music behind it and it’s really one of my best pieces. I don’t know why I got into describing something that’s not going to come out until next year. I hope people look forward to it.

Paula: Right. It sounds like your inspiration, especially during this time of COVID, has been with things that are maybe different than they were previously. Or have you spent a lot of your time playing with some new things for you?

John McEuen: I have. The book, The Life I’ve Picked, I’m hoping to get out next year as a spoken word book, only one with enhanced spoken word things, music, photos, and some video that you’ll be able to access when you download the spoken word book. Getting that together is a fun thing to do.

It’s very lonely thinking about yourself and things that you’re doing and doing stuff all the time. It’s a lonely pursuit. But it’s okay. I’ve been alone a lot. It’s lonely, but I have these visions of it going out there and getting to somebody, getting in their house.

I’ve flown over the country over the years, I’ve flown over 3,000,000 miles. Sometimes you’re going over Kansas or Oklahoma and I’d look down and wonder how many houses have a record that I’m on in them. Nitty Gritty Dirt Band got out there pretty good, and some of the other records I’ve played on, like Carolina in the Pines, and Wildfire by Michael Martin Murphy, and that gets out there.

I sit here and I make something on my computer, or I work on the vocal of something and I think, “I’m making this for somebody’s house.” I know Ron, I don’t know his last name but he’s in Kansas, Ron and his wife Marra are big fans, I know he’s going to like it. I know Dave in Arizona is going to like it. A few thousand of those. Then you wonder who you’re going to reach. It’s a fun game.

Paula: I like that. As a podcaster, I can relate. It’s kind of a lonely thing when I’m creating my own solo episodes and I never know where or who these words will ever reach. So, I can relate to all of that in kind of an interesting way. I’m sure there are other people who work on a craft at home and sometimes in their own way, we’re all such social creatures with everything.

John McEuen: Everything was in his garage, except what his brother bought, then he put it in his garage. You don’t know. You just paint because you paint. I try to capture something, do something. I’ve been very fortunate that I’ve made things that have gotten out there.

My most recent album, Made in Brooklyn, it was made in Brooklyn.

Paula: Yes.

John McEuen: Do you have that album?

Paula: Yes. I like it. It’s very good.

John McEuen: It’s the best sounding record I’ve ever played on. It came out a couple of years ago. It has John Carter Cash, Johnny and June’s son, Matt Cartsonis, David Amram, Andy Goessling from the group Railroad Earth, Steve Martin plays on a cut, John Cowan the great bluegrass singer, Martha Redbone. We had up to 14 people on one song.

It was all recorded with microphone. Not to save money, but it was the way they did it. You’d run a little bit of the song for the engineer, he would shift people around out in the studio, “You need to be closer. You need to be further. You move over here.” It was a stereo microphone on a dummy head. You couldn’t all be on one side of the stereo, so he spread it out.

Paula: That’s amazing.

John McEuen: It’s the best drum sound I’ve ever had on a recording. Kevin Twigg was the incredible drummer. It just amazed me. The first song on there, Brooklyn Crossing, has five instruments, and it was one take. All of the songs were one take, but we might have taken take two.

Paula: I know Mr. Bojangles is on that album, which is one of my favorites because my dad used to play it around the house, and he does a rather hilarious rendition of it himself. Would you tell us what made you put it on that album?

John McEuen: Bromberg does the first three verses, Matt Cartsonis does the last two verses, there’s five. Bromberg used to play with Jerry Jeff Walker for several years and they would do that song together. David Bromberg is the first guy I ever heard do it live back in 1970.

We arranged for the Dirt Band after a show to go to the Main Point Coffee House in Pennsylvania to see Jerry Jeff Walker, and he has that incredible David Bromberg playing with him, great. We got there after the show and Jerry Jeff was collapsed on the floor in the dressing room. He called it a Wild Turkey night. Bromberg said, “I know the song. Here, I’ll play it.”

We were talking about that when we finished Made in Brooklyn. I looked around and I said, “Everybody here knows Bojangles, right?” What key? How about D? D worked out. We said let’s record it. “David, sing the first verse and then the chorus, and then the next two verses, then a chorus, then Matt will do the last two so you can play that backup and do an instrumental solo, and I’ll look at everybody if they’re going to solo. First solo will be the clarinet.” That’s what we did. Okay, let’s roll.

That’s what was fun about this album.

Paula: That’s incredible. It does kind of capture that there’s a liveliness to it, and you don’t always get that on an album.

John McEuen: No. I liked recording and the process of making a record with a band, but it’s so old school. I remember one time the Dirt Band was making an album and, “Bobby, you leaving town?” Oh yeah. I’ll be back Tuesday. I have to do the bass over on the second song and I have to sing the harmony part on another song. “Oh, okay. See you when you get back.” The record was made and then one guy would go in and do a guitar part, another guy would go in and do a vocal part. Why don’t we all know the song and record it at the same time and be done with it?

This album was recorded in two days. Two long days, I will say, but everybody was into it. That’s Made in Brooklyn, it was on Chesky Records.

Chesky Records is a fine label. I called my friend at Skywalker Sound, he’s been there 25 years, and said, “Hey, Bob. I’m making an album for Chesky Records. You ever heard of them?” He said, “John, there’s only two things you need to say to Mr. Chesky.” I asked him, “What’s that?” He said, “Thank you, sir,” and, “Yes, sir.”

Paula: That’s funny.

John McEuen: He said, “I use Chesky Records at Skywalker to check my system and make sure that it sounds right,” and he does. They’re great sounding records. And it won The Americana Award from the independent record manufacturers.

Paula: It is really good. I’ll link up to that in the show notes for people if they’re curious about hearing it, because it really does have a special sound and I really enjoyed it.

John McEuen: She Darked the Sun is on that. I had John Cowan, who is my favorite singer, I’ve known him since 1974, for 10 years I’ve been trying to get him to record this song on one of his albums. I called him up to see if he was available for this and he said, “You want me to sing that song, don’t you?” I said yes. And he did it. And he sang on a couple of other things. He did a great job.

Martha Redbone did a great job. Martha and I wrote music for a song called I Rose Up, and those were words from William Blake, the British poet from the 1800s. It’s as if William Blake had moved to Appalachia and learned to play the banjo or fiddle, that’s the kind of music we put behind it. It’s really fun. When that was over, it was like we wanted to start it again.

Paula: Do you have any plans to get back together with them and do some more work?

John McEuen: The last year and the year before, one or two or three would show up at a gig and we would do stuff together, but there are no plans right now.

I’m going to go out and play solo or with just John Cable, a previous Dirt Band member. I did a show last weekend that was Les Thompson, me, and John Cable. Les Thompson is the original Dirt Band bass player, John Cable was there when we went to Russia, and then there’s me. That’s a fun thing to do.

Matt Cartsonis is the fourth member of the group I call String Wizards. No plans right now, other than some tentative jobs, maybe February, maybe March. We have to see how this plays out. My wife and I have been together since February 8th early in this year, longer than any other time in our marriage. Fortunately, it has worked out

Paula: It’s been interesting. I think for many people with such close proximity and for such a long time with the same people, it has definitely been interesting.

John McEuen: People like to think, I believe, that they are doing something important or they have an importance to the world in their life. This has changed all of that. You don’t need to go do that, because you can’t, your job is shut down or nobody is doing that. I think what’s happening, at least for me, I’m realizing how important some things are that I hadn’t paid attention to.

I don’t know how it is for you, but at the 7-11, “Hey. How are you doing? I’m glad you’re here.” The people at the grocery store, the people that put stuff in bags, Uber drivers, just a long list of things that I’m really glad work well in this country.

Paula: Right. I’m finding it really nice to be able to interact with our neighbors more. We’ve always been friendly with the people that live on both sides, but it really is one of those true points of connection. We can walk out and actually speak with them and we see them face-to-face. You know, I don’t even see my parents that often. There’s this real community here that I think has grown or changed a little bit.

John McEuen: Also, I think people are finding I just don’t have to go there, I’ll stay here and work, I’m going to sit around the house, I have book to read. I went to the Post Office today and it was like, “Wow, I’m getting out.” I got done shipping three packages and I was like, “I want to go home.” That made me happy. I’m basically happy to get on the internet and see some old friends there and stuff like that.

What makes me happiest is performing for people. I look forward to getting around to where I can make other people happy so they can do that for me.

Paula: It’s been a real treat to have you on the show. Would you like to share where people can find out about your book or about your album before I get to the last question that I like to ask everyone?

John McEuen: Sure. My book is available on Amazon, The Life I’ve Picked: A Banjo Player’s Nitty Gritty Journey. It’s doing quite well. Read the reviews, all of them, including the one-star that was written by, I’m sure, one of the guy’s ex-wives, but she is disagreed with by everybody, the other over 100 people that gave it five stars.

I’m very proud of the book. I spent a lot of years writing it. The pictures are cool. There’s pictures with everyone, from José Feliciano as a teenager and then 10 years ago playing with him in New York, not a teenager, Leon Russell, all kinds of people, Willie Nelson, I have a picture in there of Gary Hart and me and it’s a funny story.

It’s a very strange book. It sure helped me, I know that.

Paula: And then for the last question. What are three ways that you can think of to jump start joy in your life, in the world, or in other people’s lives?

John McEuen: I think making some kids laugh. I’d say just be a good grandfather. I have seven grandkids. My 26-year-old granddaughter just had a baby, so now I have a great-grandchild. That is amazing. He is so happy. I think joy is the only word he knows, he’s a happy baby.

My granddaughter said, “Grandpa, you aren’t mad that I’m pregnant, are you?” I said, “Well, I’m glad you’re married and I’m glad you’re pregnant, and I’m really glad you’re doing something for me that nobody has ever done.” She said, “What’s that, Grandpa?” I said, “Up until now, I was just Grandpa. You’ve made me Great-Grandpa. You’ve made me great. Thank you.” That made her laugh and that was fun. She’s a sweet girl.

For me, musically, I have some pieces that take people away, in a good way. I think that does it. I’d like to continue doing that. I hope that they hear it, because it’s awful hard to get heard out there nowadays. Sometimes it’s just hard to get coverage.

Just give things a chance, I guess is the word. Not just me, but anyone. Go out and experience some things. If you’ve never been to a rodeo, go to one. You might find out you like it. If you’ve never been to a comedy club, go to one. Do all these things when we’re all going out. I am not going to eat escargot, and I’m not eating oysters, but many other things are open.

Paula: Thank you so much for being on the show, John. It’s been a real delight to have you.

John McEuen: Thank you.